Today, I have the privilege of reviewing the Legacy Standard Bible, specifically the inside column reference (hardcover) edition. This review will start with general discussions about the Legacy Standard Bible and then move into reviewing this particular edition.

I hope this review can be unique in addressing some of the hurdles (or stigmas) of the LSB I have seen online and speaking to them. While you may not leave the review convinced of my reasoning, hopefully, it can aid you as you proceed in deciding whether to give the LSB a shot.

Please note: I am not a translation expert. Translation is a laborious craft that calls for admiration and respect. Praise God for faithful Christians who have translated the scriptures globally over the centuries so that others may have God’s word available to them.

What is the Legacy Standard Bible (LSB) and Hurdles

The Legacy Standard Bible (LSB from here on) is a revision of the New American Standard Bible (or NASB), specifically the 1995 edition. In fact, the LSB maintains that it is not a brand-new translation but an edition that seeks to maintain the legacy of the New American Standard Bible and its translation philosophy of formal equivalency (see: https://lsbible.org/faq/is-the-lsb-a-new-translation/). Produced by the Lockman Foundation, Three Sixteen Publishing, and the John MacArthur Charitable Trust, the translation committee revised the NASB 95 (and consulted the NASB 77) to provide “greater consistency in word usage, accuracy in grammatical structure, and tightening phrasings.”

Many have stated that the LSB is what the NASB 2020 should have been. I note this as it gives readers general insight into what they can expect should they consider picking up an LSB, a formal translation that will be familiar yet with some unique translation choices (see below). Like its predecessor, the LSB on the spectrum is more “literal” or form-based.

As hinted at already, the LSB in online discourse has encountered a few hurdles/stigmas that I think are worth addressing. One of these concerns the LSB’s marketing, which has been critiqued for heavily stressing that it is most (or more) accurate than other editions available for Christians (for one such critique, see here). This is especially highlighted when the marketing comes from John MacArthur, who is essentially the face of the project in the public eye, even if he has no role in the translation itself (which I’m not sure he does). For various individuals, it’s his baby in the public eye, which means that, of course, his baby is the cutest. For them, it comes across as “my book is the best.”

For balance, one needs to consider that a new translation in a market where we have a lot of translations will have to push hard to be recognized. Additionally, given that the publisher of the LSB is smaller compared to other publishing houses (though extremely high in quality, no doubt), this marketing (in my opinion) can be excused as other big publishers heading the CSB and ESV have quite the “monopoly” (if you will) on the Bible market. Essentially, the LSB is fighting uphill, especially since its base text (the NASB) wasn’t high in the top ten rankings over the years in popularity (example see here).

Nonetheless, the objective question about whether the marketing is correct actually moves us into other discussions about translation philosophy and the value of more dynamic translations and accuracy relative to translation goals (form or meaning). I will not delve into this here, but instead, just note that, in my view, both are good and useful. There are many good articles, videos, and resources out there on the topic, but one can begin here, here, here, and here (specifically section I). I will just say for now that if you are looking for a formal equivalence translation that prioritizes form, the LSB will be a good choice and familiar to many who already utilize the NASB.

The second hurdle is that the LSB is that it is indeed tied to John MacArthur as the “owner” (as it has been expressed online by critics) of the translation, especially with the small translation committee being from MacArthur’s Master’s University and Seminary. This undoubtedly can (and does for some) hinder the reception of the LSB for a number of reasons, the most obvious being the concern of promoting a theological angle or agenda in translation. It is generally argued that translation committees made up of more people from various theological backgrounds hold more weight and that there is a warrant for skepticism in a translation committee from the same background.

Nonetheless, in my review of passages of the LSB, I haven’t seen much translational bias on topics such as dispensationalism; in fact, I have also noted a number of individuals within the Reformed community (those who are covenantal) who have happily switched to the LSB with no complaints about the translation in this regard.

The only potential bias that stood out to me is found in Matthew 24, specifically in the chapter heading (which is the same heading used in the NASB95). Here the LSB has Matthew 24:1-14 under the heading, “The Signs of Christ’s Return.” In contrast, the ESV will have two headings here: “Jesus foretells the destruction of the Temple” and “signs of the end of the age.” You can see below a comparison of headings across translations:

From my perspective, the LSB heading could be interpreted as a potential eschatological bias (namely, one that affects a reading of the chapter), which also occurs in parallel passages (Mark 13 and Luke 21). The majority of evangelicals may not notice or take issue with the heading, while those who understand 24:1-29 (or 1-35) as being fulfilled in AD 70 will likely notice it (if you want more on that, see here and here).

All in all, this is pretty minor and (again) shared by the NASB95. The reality is that there is always a chance that bias appears in translation to some degree or another. Generally, given the LSB’s commitment to maintaining the NASB’s “legacy” and its continuity with the NASB (and the standards of the Lockman Foundation), you can trust you’re getting a good text.

That said, an interesting tidbit is that readers can find the translation committee out in the wild in social media groups such as the Nerdy Biblical Language Majors group, and “The Legacy Standard Bible Fan Group” on Facebook. Dr. William Varner is fairly active in both groups. Additionally, on the LSB website, you’ll find articles and links to their YouTube channel where they discuss the translation in more depth, and translation notes here.

My Thoughts on the Above Points

I think the LSB will be a bit locked into the conception that this is the “MacArthur Bible” unless it works to move itself away from that. Having talked to many people, this seems to be where the Legacy Bible will struggle to get a handful of new readers Reformed or otherwise. Seeing it labeled as MacArthur’s Bible or Translation is relatively common, along with individuals assuming one holds the positions of MacArthur because they have one. The lingering misconception of “so we’re making our own Bibles?” as of right now remains, and so the question is for how long? Hopefully not too long. The LSB is pretty new, so only time will tell. Nevertheless, to speak to that, if you’re one of those skeptical individuals, I’d simply encourage you to browse through the LSB website and its history. Nonetheless, we can talk a bit about the LSB translation and distinctives.

The LSB Translations and Distinctives

As previously mentioned, the LSB is a more formal translation, which, on the spectrum, would land in the same general area as the NASB.

From Mark Ward’s Article linked above (evangelical textual criticism)

When it comes to the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts, for the Old Testament, the LSB utilized the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (along with consideration of the Dead Sea Scrolls). For the New Testament the LSB utilizes the 27th edition of Nestle’s Novum Testamentum Graece (interesting choice) but “supplemented by the 28th edition in the General Epistles.” Additionally, “on every variant reading, the Society of Biblical Literature GNT as well as the Tyndale House GNT were also consulted.” Note: I didn’t observe any discussion on the role of the LXX in the process or the Latin Vulgate.

The LSB’s distinctives that are generally noted are 1) the use of Yahweh instead of the traditional “LORD,” 2) translating the Greek term doulos consistently as slave, and 3) capitalizing pronouns referring to deity. These are not the only distintives within the LSB, but they receive a good deal of air time.

On the use of Yahweh: Contrary to many other English translations, the LSB translates the divine name as “Yahweh.” Furthermore, the LSB renders the shortened name “Yah” when appropriate as well. This is a unique feature in this English translation, as the only ones I can recall (I know there are a couple more) that do this are the WEB and HCSB.

Generally, the divine name (or the Tetragrammaton; YHWH) is rendered as small-caps, “LORD,” in English translations. Whether or not this is a good translation choice is debated. Some argue the name ought to be translated as “LORD” on the basis of things such as the Greek translation of the OT translating the term as “Lord” and those Greek texts being used by the apostles in the New Testament. In other words, why didn’t the Greek texts used by the apostles transliterate the divine name in Greek if it were appropriate to do so? Another argument is the charge that the pronunciation of “Yahweh” is guesswork. Others think that just putting the Tetragrammaton (YHWH) itself would have made for a better choice rather than asserting a specific pronunciation. The CSB, when moving away from the inclusion of Yahweh originally featured in the HCSB, states these two reasons for the decision (among four in total),

“Third, consistent feedback from readers showed that the unfamiliarity of “Yahweh” was an obstacle to reading the HCSB. For example, many reported that they felt “Yahweh” was an innovation, and they misunderstood the intent behind using the formal name of God. A translation that values accuracy and readability was thereby limited by a translation choice that did not provide clarity to the reader.

Fourth, when quoting Old Testament texts that include an occurrence of YHWH, the New Testament renders YHWH with the word kurios, which is a title (Lord) rather than a personal name. With this precedent in hand, most English translators have chosen to render YHWH as “Lord” rather than “Yahweh.”

See the full page, https://csbible.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Translation-Decisions-QA.pdf.

Still, the use of Yahweh in the text is an alluring pull for many individuals, and scholars have generally agreed for quite some time that “Yahweh” is appropriate in terms of pronunciation. The question of familiarity raised by the CSB seems self-fulfilling to a degree (lack of familiarity from a history of using Jehovah or “LORD”), with the issue of the New Testament being beyond my discussion here. Personally, it was the use of Yahweh in the Old Testament that eventually led me to want to give the LSB a try since I had read “LORD” as Yahweh anyway. That said, this decision will be of interest to those deciding on the translation as the divine name occurs nearly 7,000 times in your Old Testament – it will stand out.

One observation (which I have emailed the LSB team about) concerns the shortened “Yahweh,” “Yah.” As the website notes, “In addition to Yahweh, the full name of God, the OT also includes references to God by a shorter version of His name, Yah. By itself, God’s name “Yah” may not be as familiar, but the appearance of it is recognizable in Hebrew names and words (e.g. Zechar-iah, meaning Yah remembers, and Hallelu-jah, meaning praise Yah!). God’s shortened name “Yah” is predominantly found in poetry and praise.”

For example, in Psalm 104:35, the LSB states, “Let sinners be consumed from the earth, And let the wicked be no more. Bless Yahweh, O my Soul. Praise Yah!” (My italics). Most translations will render the Hebrew phrase as “Praise the LORD.”

What is curious, however, is that in Revelation 19:1; 3; 4; 6, the term is still transliterated as “hallelujah” (ἁλληλουϊά)in the LSB rather than being translated as “praise Yah” in a similar vein. To be fair, I think the only version I have seen that doesn’t transliterate the term here is the New World Translation (a translation which I obviously do not endorse), of course, with “Jehovah.” (“And right away for the second time they said: ‘Praise Jah!'” Revelation 19:3, NWT).

Nevertheless, since the New Testament utilizes Greek texts of the Hebrew Bible when quoting it and translates the divine name as Lord (κύριος, kurios), the LSB translates those OT citation texts as “Lord” when the divine name (as “Lord”) occurs.

“The LSB maintains the translation of ‘Lord’ in the NT for the same reason it upholds Yahweh in the OT: because that is what is written in the original text.”

The reasoning is sound, though I have a nitpick critique here. It seems to me that it makes a bit of extra work to show when the divine name in the Old Testament is being applied to Jesus because of the different word usage. Used to you could say, “See that ‘Lord’ in both texts? Well that’s the divine name.'” While you still have to explain it, it’s less of a leap compared to “this Lord in this OT citation, is that ‘Yahweh’ in the OT.”

Either way, in those cases, “when ‘Lord ‘ explicitly translates Yahweh in a question of the OT, a footnote is provided stating such.” (in the Inside Column Reference edition, my Verse by Verse 2 Column edition says this in the preface but doesn’t have the footnotes). I think having the footnote pointing out that the text translates Yahweh is brilliant. However, I do wonder if a different format could be used to make it pop more such as putting Yahweh in brackets where the translation occurs.

All this aside, the bottom line of the use of “Yahweh” is that seeing the divine name in the text is wonderful. As I said, I already read the text that way when seeing “LORD,” and now seeing it in the text is something special. It stands out to say the least.

| LSB | ESV | CSB | |

| Isaiah 1:24 | “Therefore the Lord, Yahweh of hosts, the Mighty One of Israel declares…” | “Therefore the Lord declares, the LORD of hosts the Miught one of Israel” | “Therefore the Lord God of Armies, the Might One of Israel Declares” |

| Psalm 23:1 | “Yahweh is my shepherd, I shall not want” | “The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want.” | “The LORD is my shepherd; I have what I need.” |

| Deuteronomy 6:4 | “Hear, O Israel! Yahweh is our God, Yahweh is one!” | “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one.” | “Listen, Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one.” |

On doulos: Point two can be further examined in detail in other discussions on the LSB; I won’t speak to this beyond stating that I am happy to see the term appear in Philippians 2:7, given its significance in the overarching context. You can further explore this translation choice here starting around the 6:30 mark. It is worth noting that others (such as the ESV) do not render doulos as “slave” across the board (see the relevant section of the preface here, see also the CSB’s preface).

On capitalizing pronouns referring to deity: Following the NASB, the LSB states, “personal pronouns are capitalized when pertaining to Deity. While descriptions about God are not capitalized, those which are used indisputably as direct titles for God are.” This textual feature is one that I know many people enjoy and like in particular. It is one that I am generally indifferent to, but I have a couple of thoughts on it.

Generally, translations have not capitalized pronouns because the original texts simply don’t do such (and the practice is fairly recent historically speaking) and because, at times, it can be difficult to ascertain who a pronoun is referring to (a classic example being Ruth 2:20, “his”). This means, at times, capitalization is an interpretation of a given text. However, the LSB states that it capitalizes pronouns where it is indisputable, and “if there was any doubt, they either left it in lowercase or put a footnote to indicate this.” This is actually seen in the Ruth 2:20 example where the LSB does not capitalize the ‘his.’

Still, in other cases capitalization can lead to some confusion, particularly where there is double fulfillment. The LSB in Psalm 2, for example, capitalizes pronouns because of their [proper] Christological applications. However, the danger is jumping to that Christology too soon and missing the immediate contexts/applications to David and his seat. Will capitalization do that? I’m not sure. While the LSB makes it clear that on debated passages, they don’t capitalize pronouns, it does additionally beg the question of whether those lowercase occurrences will confuse individuals who see those pronouns as referring to God (since others will be capitalized). While the approach of “we do it when certain” is admirable, and I like this approach, I think the best would be to not capitalize pronouns and avoid the potential confusion and possibility of adding the interpretation altogether.

Small caps for OT citations: The LSB’s New Testament will use small caps for OT quotations (or obvious references). For example, “and that EVERY TONGUE WILL CONFESS that Jesus Christ is LORD, to the glory of God the Father.” (Philippians 2:11). This feature is a carryover from the NASB, and I generally enjoy it…in print. I have a love/hate with it in digital. The hate aspect is when you want to copy/paste from a digital, and all of a sudden, you’re dealing with all caps in your document! It drives me a little crazy, but maybe I’m missing out on some feature where that formatting doesn’t follow you.

Italics: Like the NASB, the LSB places words in italics when those words are not found in the original language but are implied by the original language. This is a win and a great feature that gives you transparency and insight into what a translation is doing.

Bonuses that stood out to me:

Sanhedrin: The LSB uses the term “Sanhedrin,” which occurs roughly 20 times in the NT text. While the NET, CSB, Berean Study Bible, and NIV include the term Sanhedrin, other translations, such as the NRSVeu, ESV, NLT, KJV, and ASV, do not. Generally, the term is rendered in those latter translations as “the council” (see Matthew 5:22 for one example). The Sanhedrin was the name of the supreme religious, political, and legal council in Jerusalem in the period of the New Testament. While one could get the gist of this with the translation of “The Council,” it is a welcomed rendering that moves students to study the historical context. Transliteration of other names occurs, and Sanhedrin is a welcomed addition in my mind.

Only Begotten: The LSB has translated the occurrences of monogenēs (μονογενής) in John’s gospel as “Only-begotten” while many other modern translations (if not all?) have moved to “only,” “only unique,” and “one and only.” This stands out to me in particular and I really like it. The LSB does add in the footnote, “or unique, only one of his kind.” but retains the “traditional” rendering of the term. This is a good time to remind you that the LSB translator notes (for the NT and Genesis) can be accessed here. On John 1:14 you’ll find the full explanation behind why the LSB retained “only begotten” but here is a piece,

“Further support for the legitimacy of this understanding is found in the universal attestation of the early church fathers, and also in recent scholarship (e.g., Charles Lee Iron’s book, Retrieving Eternal Generation and Wayne Grudem’s 2nd ed. of his Systematic Theology), as many scholars are moving back towards this more traditional view (cf. KJV) of μονογενής (monogenēs) in John’s writings.”

| LSB | NRSVue | ESV | |

| John 1:18 | “No one has seen God at any time; the only begotten God who is in the bosom of the Father, he has explained Him.” | “No one has ever seen God. It is the only Son, himself God, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known.” | “No one has ever seen God; the only God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known.” |

To Cut a Covenant: The LSB translates כרת (karat) as “cut” rather than made. This can be seen in a number of texts such as Genesis 15:18, “On that day Yahweh cut a covenant with Abrah.” This occurs roughly 50 times in the Old Testament, while other translations, such as the ESV and CSB, will state, “The LORD made a covenant.” “To cut,” a covenant is certainly a significantly faithful rendition and a standard idiomatic expression of initiating a covenant in the Old Testament. [1]

Of course, these are not the only distinctives in the LSB, and I can’t go through them all. So we’ll stop there, and I’d encourage you to see some other reviews like this one for more distinctives in the LSB.

My Thoughts on the Translation

By this point, I have worked through a good chunk of the Biblical text in the LSB (I haven’t completed the OT yet in it), and I can say that I found myself enjoying the LSB to the point that I actually picked up a less cumbersome edition (two-column verse by verse) for more frequent use.

In my readings, I have found the LSB to be a well-flowing text, with only a few times where I saw a text and thought it was ‘clunky.’ In that same vein, and as is expected, there have been spots where I’m not sure I like the translation choices (like “cleans” in John 15:2, though I know they are trying to show the play on words) and yet at other times I really appreciate the consistency (like “seed” in Galatians 3). In general, I’m a multi-translation guy; I hardly consult just one translation in study and have found the LSB being easily welcomed into my rotation, essentially, an updated NASB. For daily readings, I have found myself gravitating to the LSB here and there.

That said, if you’re looking for a solid formal translation, the LSB is worth checking out. You can test-run it on apps like the Bible app and Accordance Bible Software for free. If you decide to pick up a physical copy, 316 Publishing offers a variety of formats to choose from.

On the flip side, if you have a NASB 95, I’m not entirely convinced you’ll find the update worth the extra money. Using the compare feature on Bible Hub or in Accordance, you can compare the NASB 95 and LSB side by side to see why I say this. Some of the distinctives I’ve mentioned above will make or break it for those considering a jump from the NASB95 to the LSB. That said, I know that many have made the jump simply on the basis of the use of “Yahweh” in the Old Testament, which I understand given that is what pulled me in!

All in all, I really enjoy the LSB. Whether it replaces the ESV as my primary/casual English translation remains to be seen. Perhaps I’ll update the post or website should it ever come to that.

The LSB has the opportunity to make some good editions of the text some of which I hope to see: Single Volume Readers, Full (Translators) Notes Edition, a Study Bible (aside from the recently announced MacArthur), and a polyglot.

Inside Column Reference

With discussions on the translation itself wrapped up, I can speak to the specific edition I received, the Hardcover Inside Column Reference. The description and specifications (from the website) of which are as follows:

“The Inside Column Reference Edition of the LSB has over 95,000 references and over 14,000 footnotes conveniently placed on the inside column to allow maximum space for Bible text. It also contains a concordance and full-color, detailed maps. It comes in both indexed and non-indexed editions.

Features:

- Easy-to-read, large 11 point font

- Black letter text with red for book titles, running headers, chapter & page numbers

- Line matched, single column, verse-by-verse typeset

- Over 95,000 cross references and over 14,000 translation footnotes

- 40 gsm Bible paper

- 1,696 pages

- Smyth-sewn with overcast stitching

- One double-sided satin ribbon

- 90-page concordance with over 16,000 Scripture references.

- Tables for weights, measurements, and monetary units

- 8 full-color maps

- Printed and bound in Korea”

The first thing I should note is the size, 9.25″ x 6.5″ x 1.69″, which isn’t something I like to carry around (one of the reasons I also picked up the VBV edition), but I know others don’t mind. For me, however, this edition has become a “desk edition,” and a wonderful one at that. The typography is beautiful and the font size can be comfortably looked at on a book stand or desk without needing to be too close to the book itself. The binding is great, and it lays flat, but it’s also just a good-looking hardcover, which I always appreciate.

It took me some time to get used to the verse-by-verse layout, but what I love about this edition is the use of red for titles, headers, chapters, and page numbers. They just look great. A bold verse number indicates paragraph breaks, and the notes’ organization is fantastic.

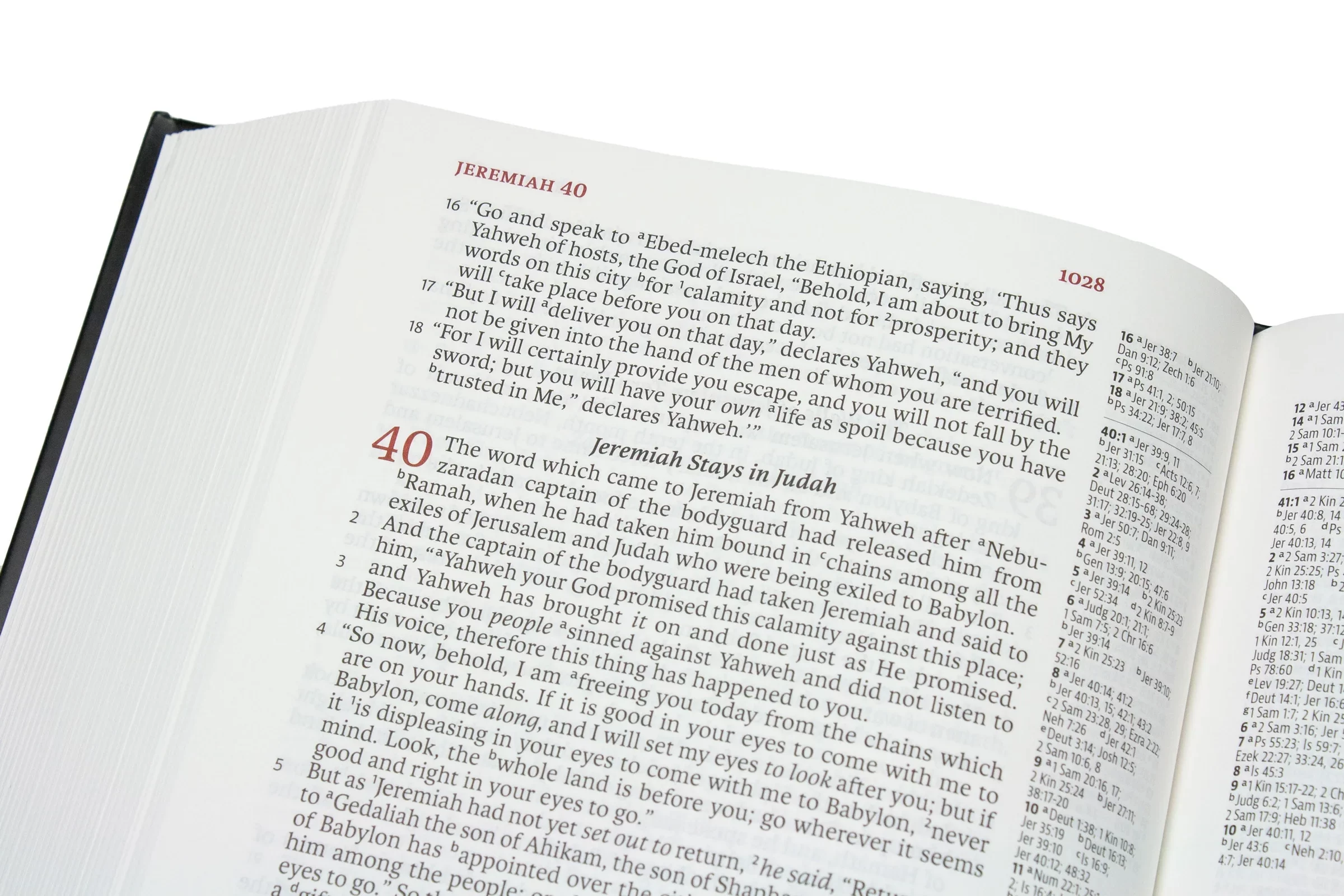

As the features note, there are over 95,000 cross-references and over 14,000 translation footnotes. In the above picture, you can see a bit of the layout: cross-references are featured at the top of the page, with line breaks at new chapters. Translation notes are featured at the bottom of the page, also with line breaks at new chapters.

Here is the layout in more detail:

It features a 90-page concordance, three columns per page, consisting of keywords with synonyms and related words and their corresponding scriptural references. Furthermore, it has 8 full-color maps that are just beautiful. The paper quality is high, and the ghosting is minimal. This is just a great Bible, and I find the layout of the inside-column reference notes particularly appealing. Not only is the layout more appealing than some of the more bottom-of-the-page blocks I’ve seen, but it’s easier on the eyes with the typography giving my Leather ESV with Creeds and Confessions a run for its money.

All in all, this is just a great reference Bible. Having received two LSBs, one being this hardcover and the other being the Goatskin Verse by Verse 2 column, I can simply say that the folks over at 316 Publishing are putting out quality materials. If you’re looking for a reference edition of the LSB, I don’t think you’ll regret picking up this edition at all, which is offered in different formats.

Conclusion

As I stated above, all in all, I really enjoy the LSB. It is a smooth, formal translation, and the publisher is doing an excellent job putting out quality editions of the text. Whether it replaces the ESV as my primary/casual English translation remains to be seen. Perhaps I’ll update the post or website should it ever come to that.

I hope you found this review helpful or at least interesting and let me know your thoughts on the LSB!

[1] Kingdom through Covenant by Wellum and Gentry, “Animals are slaughtered and sacrificed. Each animal is cut in two, and the halves are laid facing or opposite each other. Then the parties of the treaty walk between the halves of the dead animals…What is being expressed is this: each party is saying, “If I fail to keep my obligation or my promise, may I be cut in two like this dead animal.” The oath or promise, then, involves bringing a curse upon oneself for violating the treaty. This is why the expression “to cut a covenant” is the conventional language for the initiation of a covenant in the Old Testament.” p. 185.

12 Responses

A really good and thorough review. I never would have given a new translation much more than a casual glance had I not read this. Thanks Mike

Glad to hear you enjoyed the review! Thanks for leaving that feedback!

I will stick, stay, memorize, believe and obey, by the grace of God, THE KING JAMES BIBLE. I am not smart enough to memorize several different translations. I understand God’s Word is settled forever in Heaven (Psalm 119:89) but GOD also promised to keep and preserve His Word (Psalm 12:6,7. And, “Where the word of a king is, there is power”(Ecclesiastes 8:4). Also, the ones that promote this new “Bible” also believe(or at least many of them do) that God commands some to believe something that He Himself made impossible for them to do.

The King James is a beautiful translation despite its many problems, I don’t blame you for sticking with it especially for memorization.

Recommend you do same compare/contrast using the Geneva Bible (1599). This is the Holy Bible brought to America by the Pilgrims, and wasn’t a translation under the “watchful eye” of an earthly king and his advisors (KJV).

Yeah, I’m familiar with the Geneva and actually use a 1599 edition put out by Tolle lege on occasion. It’s very similar to the KJV though its background is certainly more interesting especially as the first ‘study Bible.’ It’s my preferred TR edition.

Hello i was considering picking up a copy of this translation but i am unable to use the apps you suggested as i only have a flip phone i’m unable to check so i was wondering does the LSB refer to the place of the crucifixion of Jesus occurred as The Skull, Golgotha, or Calvary? I’m curious i have been considering importing a copy since the physical release was announced but alas i’ve been unable to find anywhere that states what term they’ve used. I have tried several times getting in contact directly with the publisher but they never responded to my emails so i politely request you can tell me this info.

It reads in relevant texts, “a place called Golgotha, which means place of a skull.”

Hey Nick! thanks so much for your review I really appreciated it. I actually go to Grace Community Church, but I wanted an honest review of this version. I am a leaky dispensationalist if that at all, but I really appreciate the sound deep theological teaching, pastoral care, and Christian fellowship and accountability I’ve gotten there, so really have no plans to leave lol. I’ve become slowly and slowly more attached to reformed teaching, and wanted a good bible, without the commentary, and though I looked into other versions, ultimately I love this translation. I appreciate your review so much, I’ve reached out on IG several times, and you’ve always been really helpful. Really appreciate your resources brother.

Great review! Just curious if the LSB has replaced the ESV as your primary English Bible? Or if that’s still up in the air? Either way, many thanks, and blessings in the Lord! 🙂

Actually, after using both for awhile now, I found I still prefer my ESV and don’t use the LSB much. They’re both great still and so I don’t want that to dampen folk who use the LSB.

Thanks for the review. I had on my to-do list to check this translation out. I currently have 8 translations on my screen when I am studying in BibleWorks. The more literal ones are NAS and YLT. ESV has replaced NET as my favorite New Testament. I still prefer NIV (the older version) for the Old Testament, for readability (I know Greek but not Hebrew). Since I can’t get LSB into BibleWorks, I am unlikely to reference it very often, but it is good to know it’s there.

By the way, when I read the OT (and especially when I pray through the Psalms) I do use the name Yahweh when I see LORD. Considering how many times it is found in the OT, it seems to me that God WANTED us to call him by name!